https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/sep/16/the-greek-passion-review-martinu-grand-theatre-leeds

Blog

Review of Greek Passion from The Stage

huslav Martinu’s The Greek Passion may be more than 60 years old, but its contemporary relevance is stinging.

The Czech composer’s opera, presented by Opera North in its original 1957 version, tells the story of a group of refugees who flee to a Greek island where the villagers are performing a Passion Play for Easter. They face a hostile reception, but when the performers begin to take on aspects of their characters, passions are inflamed.

Charles Edwards’ set is both minimal and imposing, consisting of a huge bench-like steps structure, but it’s the representation of the refugees that really impresses. The Opera North chorus plays the roles of both the locals and the newcomers, holding stark white mannequins in their arms to give them a voice. When a refugee dies, the figure is hoisted up to the sky and the effect is eerie and unsettling.

Christopher Alden’s production makes some modern additions to Martinu’s music – there are touches of polka and folk to be heard, as well as a knee-slapping wedding

song with its own synchronised dance routine. It’s also necessarily dark. Nicky Spence is a tormented figure as Manolios, the ordinary villager struggling to be worthy to play Christ, while Magdalena Molendowska’s affecting soprano brings out the pain in her portrayal of the widow Katerina.

There are some updates to the text too – an exclamation of “bloody vegans!” receives the biggest laugh of the night. Yet this remains an opera with a message – the phrase “give us more of what you have too much of” hangs over the stage towards the end of both halves. Opera North has produced an accessible and powerful production that hits home hard.

Review of Greek Passion in the Sunday Times

Opera review: The Greek Passion, Opera North; Don Giovanni and Werther, Royal Opera

Martinu’s patchy Passion gets a powerful Opera North treatment

Holding pattern: the Opera North chorus in Martinu’s The Greek Passion

TRISTRAM KENTON

The Sunday Times, September 22 2019, 12:01am

In typically adventurous style, Opera North opened its 2019-20 season with a regional touring production of Bohuslav Martinu’s operatic swan song, The Greek Passion, based on Nikos Kazantzakis’s epic novel Christ Recrucified. This opera was famously rejected in 1957 by a subcommittee of the Covent Garden Opera Company, much to the consternation of its then music director, the great Czech conductor in exile Rafael Kubelik.

Kubelik clearly had an empathy not only with his compatriot’s score, but also with the subject matter: at Eastertide, village elders in Lycovrissi, Greece (under Ottoman rule in the novel), choose members of the community for leading roles in the annual Passion play. Their spokesman, the priest Grigoris, warns of the influx of a tribe of refugees seeking asylum from their Turkish oppressors. As the villagers take on characteristics of the parts they are playing, the shepherd Manolios, representing Christ, preaches charity and compassion towards the incomers. Grigoris denounces him as an apostate and incites the Judas character, Panait, to murder him. The refugees, realising they have lost their champion, move on.

Hugh Canning

It’s a powerful narrative, certainly, packed with interesting characters and biblical analogies — the widow Katerina, chosen to play Mary Magdalene and pursued by Panait/Judas, is physically attracted to Manolios — and it is splendidly performed in Leeds, conducted by Opera North’s music-director elect, Garry Walker, and simply staged by Christopher Alden, with enough political resonance to suggest analogies with our own time.

If there is a problem, as in 1957, it is with Martinu’s large-scale yet rarely unforgettable score. The prolific composer, adept in every genre, clearly struggled to find a distinctive “voice” in this cosmopolitan work, set to his own English libretto. For much of the evening, thanks to the heroic and touching central performance of Nicky Spence as Manolios, I thought fondly of Britten’s Peter Grimes, written a good decade earlier, but now a standard repertory piece, while The Greek Passion still hovers on the fringes.

Even so, this is one of ON’s great company shows, featuring a supporting cast that includes stalwart regulars such as Paul Nilon (Yannakos, the pedlar who plans to rob the refugees), Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts (Panait), Stephen Gadd (Grigoris) and John Savournin (the priest Fotis, the leader of the refugees). Magdalena Molendowska sings clear English words as a big-voiced Katerina. The chorus are so good, one wishes they had better music to sing.

Review of Greek Passion in The Daily Telegraph.

› Culture › Opera › What to See

The Greek Passion, Opera North, review: is Martinu's final masterpiece the most moving opera of our time?

Nicky Spence as Manolios in Opera North's The Greek Passion, its first British staging in 20 years CREDIT: TRISTRAM KENTON

Follow

By John Allison

22 SEPTEMBER 2019 • 4:34PM

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/opera/what-to-see/greek-passion-opera-north-review-martinus-final-masterpiece/ 1/4

23/09/2019 The Greek Passion, Opera North, review: is Martinu's final masterpiece the most moving opera of our time?

From hard hearts to deaf ears, The Greek Passion has never enjoyed an easy reception. Originally commissioned by Covent Garden in the late 1950s, it was rejected then — tensions over Cyprus may have played their part — and has made only sporadic appearances in Britain since. Yet Opera North's new staging, the first in this country in 20 years, shows how Bohuslav Martinu's final operatic masterpiece is perhaps the most moving and topical opera of our time.

Based on Nikos Kazantzakis's 1954 novel Christ Recrucified, its subject is exile, and all the elements of Martinu's own scattered life and diverse stylistic experimentation come together in the piece. That is especially true when Ales Brezina's reconstruction of Martinu's original score is used, as at Opera North, rather than the heavily reworked version that premiered after the composer's death in 1959.

There is no contradiction between its intricate dramaturgy and simple honesty, at least not when they are reconciled so sensitively by the director Christopher Alden and conductor Garry Walker. Alden's production is timeless, yet a few details pin it to the recent past. A serenading shepherd's pipe becomes a cassette player, and Yannakos's donkey is a bicycle — we are no longer in the Greek village of Lycovrissi, as some gratuitous alterations to the libretto (prawn cocktail crisps, anyone?) confirm.

Nicky Spence as Manolios, Rhodri Prys Jones as Michelis, Paul Nilon as Yannakos and Richard Mosley-Evans as Kostandis CREDIT: TRISTRAM KENTON

Playing down the political aspect by not making connections with the current refugee crisis, the production plays up the religious element and — with it — the church's hypocrisy. The two intersect in the chorus's powerful, angry Kyrie Eleison at the end of Act 2.

Charles Edwards's set is dominated by movable raked seating, representing perhaps the refugees' mountain slope, a Greek theatre or simply an abstract frame. The black-clad

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/opera/what-to-see/greek-passion-opera-north-review-martinus-final-masterpiece/ 2/4

23/09/2019 The Greek Passion, Opera North, review: is Martinu's final masterpiece the most moving opera of our time?

chorus carries white plaster effigies, standing for refugees deprived of a voice, and the motto "give us what you have too much of " becomes a feature of the design.

Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts as Panait, Paul Nilon as Yannakos, Magdalena Molendowska as Katerina, Nicky Spence as Manolios, Richard Mosley-Evans as Kostandis and Rhodri Prys Jones as Michelis CREDIT: TRISTRAM KENTON

Such simplicity allows the music speak for itself. Walker, in his first production since being named Opera North's music director designate, holds the potentially stark and sprawling score together tautly, bringing out Martinu's trademark radiance.

The excellent cast is led by Nicky Spence's Manolios, a real outsider whose generous, unforced tenor conveys the sincerity of the shepherd chosen for the role of Christ in the passion play. As Katerina, the village Mary Magdalene, the soprano Magdalena Molendowska sings with glowing lyricism. Among many others, Paul Nilon's Yannakos and Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts's biker Panait stand out. The two rival priests contrast strongly, John Savournin as the refugees' leader Fotis, and Stephen Gadd as Grigoris, the lupine defender of the status quo.

Until November 16, in Leeds, Newcastle, Nottingham and Salford. Tickets: operanorth.co.uk (http://www.operanorth.co.uk/)

Contact us

About us (https://corporate.telegraph.co.uk/) Rewards

Archive (https://www.telegraph.co.uk/archive/) Reader Prints (http://telegraph.newsprints.co.uk/) Branded Content

Opera North announces new musical leadership

PUBLISHED ON JUNE 24, 2019

We are delighted to announce two significant appointments to our artistic and musical leadership with immediate effect, marking an exciting renewal in Opera North’s life and future.

Garry Walker becomes Music Director designate and will take up his post from the 2020/21 season in August 2020. As Music Director, Garry will head the musical leadership of Opera North and joins the artistic management alongside General Director, Richard Mantle, and Director of Planning, Christine Jane Chibnall.

Garry Walker, Opera North's Music Director designate © Jack Liebeck

Garry is currently Chief Conductor of the Staatsorchester Rheinische Philharmonie in Koblenz where he will retain some responsibilities until the 2021/2022 season and therefore there will be a period of transition between the two organisations. Once he is in post, he will conduct two opera productions and several symphonic concerts during each season and will become embedded in the life of the company at all levels and across the diversity of the Company’s work.

Garry’s recent work for Opera North has included an impressive and powerful Billy Budd and the double bill Gianni Schicchi & The Rite of Spring. He is due to open Opera North’s upcoming mainstage season in September 2019, with a new production of Martinů’s The Greek Passion.

As Principal Guest Conductor, Antony Hermus, who who made a revelatory debut conducting Opera North’s production of Tosca in 2018, will build on this strong relationship, contributing to the artistic vision of the company and conducting one opera production each season as well as symphonic concerts, whilst retaining his current position as Principal Guest of the North Netherlands Orchestra and continuing his burgeoning international career. Antony is scheduled to conduct The Marriage of Figaro in the 2019/20 season.

Antony Hermus, Opera North's Principal Guest Conductor

Richard Mantle, General Director, Opera North, said:

“I am delighted to welcome Garry Walker to Opera North as Music Director, following a two year recruitment process for this key artistic leadership role. He will be a great colleague and will bring clear, resilient and mindful leadership, driving and inspiring high musical standards as well as being fully alive to our ethos and aspirations, as we move forward into a new chapter in the life of the Company.

“The addition to the team of Antony Hermus as Principal Guest Conductor is also an exciting prospect and creates a new structure which builds on the established musical and artistic strengths of Opera North. His positivity and dramatic flair will be an undoubted asset to the Company and we look forward to working more closely with him over the coming seasons.

“We have already had the privilege of working with these two musicians over recent years, who each bring valuable yet complementary strengths and experience to the Company. These appointments to our core team will further enhance our commitment to innovation and excellence into the future.”

Garry Walker, Music Director designate, Opera North said:

“I’m hugely honoured to become Music Director of Opera North, and excited to maintain and advance the already enormously high artistic standards achieved. It is an organisation I have a twenty-year relationship with, and its warmth, inclusivity and genuine company ethos – something commented upon by so many visiting artists – is one of the key characteristics which has drawn me to Opera North over the years.

“Opera is the ultimate team game, with so many individuals in so many differing disciplines coming together to contribute to the overall success of performances. I look forward to putting the music and the storytelling at the centre of what we do, and I hope to bring my energy and love for the dramatic power of opera to our audiences, both on and off the podium.”

Antony Hermus, Principal Guest Conductor, Opera North, said:

“From my very first encounter with Opera North I felt such enormous energy, drive and commitment for our wonderful artform. As Richard Wagner said: “Music is the language of passion”, and I look forward to sharing this common passion for music and opera with all our fantastic singers, musicians and indeed the whole Company, working together to inspire our audiences to the maximum!”

Repeat of Scheherazade in Neustadt

Thanks again to m’colleagues at the Rheinische Philharmonie. Super playing all round.

Last Music Institute Concert of 18/19 review

Not bad at all.

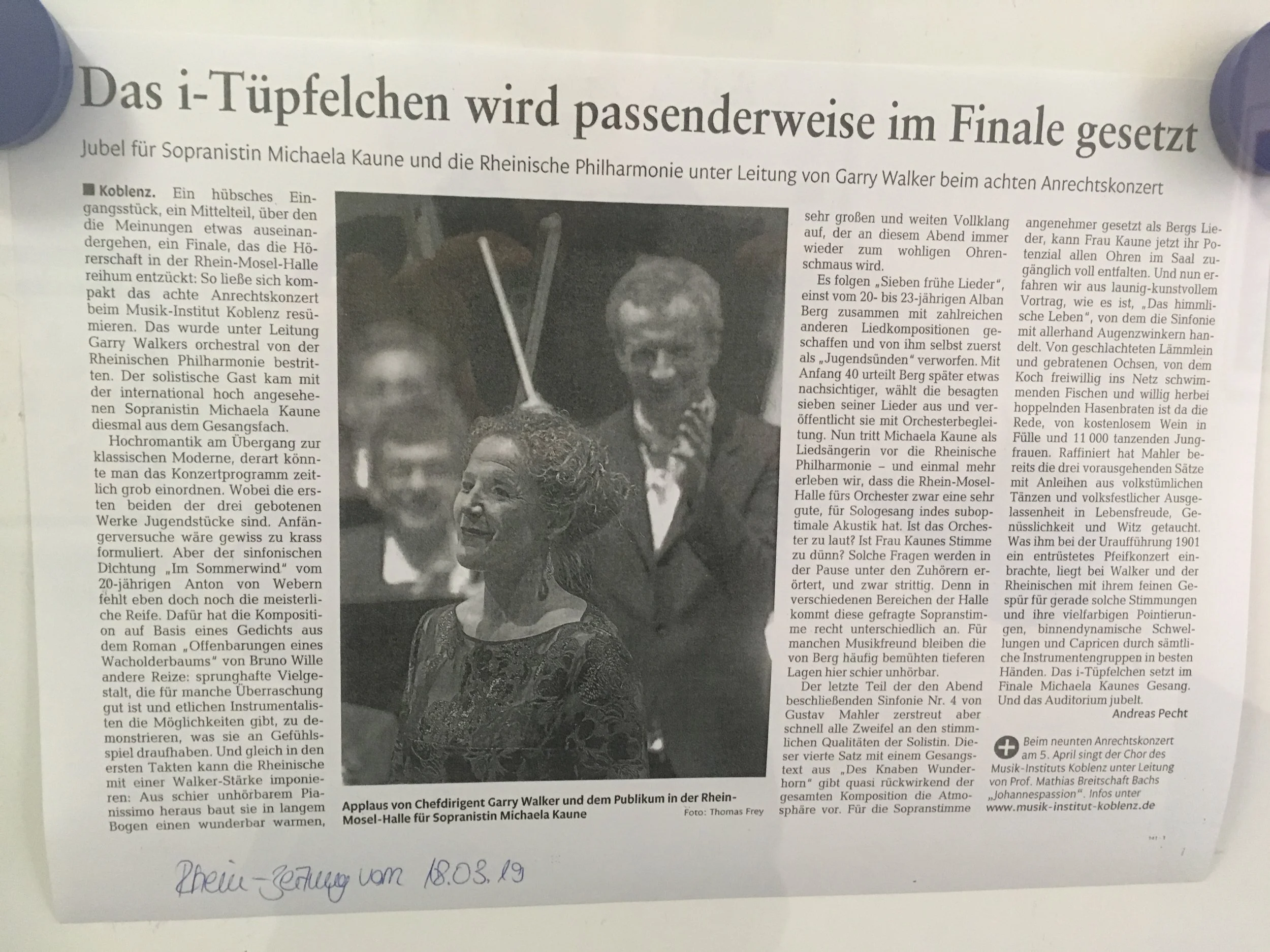

This was quite a concert.

Webern, Berg, Mahler.

Sold out.

Karlsruhe Concert Crit.

Another great Crit for Opera North Schicchi/Rite of Spring double bill.

https://www.spectator.co.uk/2019/03/opera-norths-rite-of-spring-shows-the-advantages-of-confining-the-music-to-the-pit/

Gianni Schicchi crit from The Times.

Karlsruhe crit.

Koblenz American Project

Pretty damn good....

Ben Lomond

So rare to get to the hills at the moment. Fortunate that when I do, I get weather like this!

View across Loch Lomond to Loch Sloy and Arrocher.

Visibility was exceptional, with views to the Paps of Jura, Ben Nevis, Ben Lawers and Arran....even Ailsa Craig was clearly visible.

Because we went up quite late, we met the hoards descending, but had a reasonably quiet summit.

Ben Nevis and Glencoe in the far distance.

Looking towards Loch Tay peaks and beyond.

Descent was very much by torchlight. Was amazed to find so many people without them. Always love descending by night; all the lights along the Loch twinkling away, the moon rising...magical.

And another good crit.

Always very very fortunate to work with musicians of the quality of Alexander, Guy and the Mirglieder of the Rheinische Philharmonie

Another great crit from Koblenz; this one is a real tribute to the orchestra.

TLS Crit of The Skating Rink

Date: 20 July 2018

Page: 20

Circulation: 32166 Readership: 96498

Size (Cm2): 767

AVE: 2531.10

Display Rate: (£/cm2): 3.30

ARTS

Mythical spaces

Opera, from an organ room to an ice rink

GUY DAMMANN

Claude Debussy

PELLÉAS ET MÉLISANDE Glyndebourne Festival Opera, until August 9

David Sawer

THE SKATING RINK Garsington Festival Opera

The Glyndebourne Festival’s new pro- duction of Pelléas et Mélisande, con- ducted by Robin Ticciati and directed by Stefan Herheim, is the company’s fourth staging of the work, timed in celebration of the centenary of the composer’s death. The curtain opens, straight away, to reveal an oddly familiar space, in both senses of the term. A family and their servants are gathered in a great hall, overlooked by grand paintings and, more conspicuously, a large organ. They surround a kind of altar on which is laid the body of young woman, their apparent mourning led by Prince Golaud. In the minute and a half or so of music before the action formally begins, the com- pany dissolves, leaving Golaud, dressed in plus fours and a tweed hunting coat, lost in thought, to chance on the same young woman, equally lost and, with streaks of blood descending from her eyes down her cheeks, apparently blind, but now nonetheless living and breathing.

To a sceptical eye, much of this will seem ludicrously arch, particularly the set, which is a detailed replica of Glyndebourne’s organ room, an extension to the Elizabethan manor constructed by John Christie in the 1920s to accommodate the family’s increasingly ambitious musical life. The instrument, which looms almost preposterously large in the house (it is apparently the largest domes-

tic organ in Britain), has an even more power- ful presence on the stage, filling the entire width. This, and the way many details are crammed into the opera’s opening moments so we are equipped with the information we need to know, or to set aside, in order to understand what on earth has been done with the original scenario (in this case, “une forêt”), make for a somewhat worrying beginning. That said, Ticciati’s handling of the opening’s music is radiant, exquisitely shaded and calmly paced.

In the second scene, the rhythm of the stag- ing seems easier to grasp. The organ has shrunk to more homely proportions and the lighting acquired a more cheerful aspect, ren- dering visible the paintings as replicas of those hanging in the actual organ room next door. More important, however, is the way the movement of the singers becomes more immediately visible. This quality is particu- larly noticeable after Pelléas – dressed in a light, striped suit with a blue bow (possibly inspired by a photograph of Debussy picnick- ing) – has asked his grandfather’s permission to leave the castle to visit his dying friend. The answer is that he must wait at home because no one knows how Golaud’s return, with the mysterious princess, will affect the life of the family. The music at this point is full of dark shadows, but as the interview con- cludes it lightens until a beatific violin solo floats high above the swaying harmonies. At this moment on stage, Pelléas, his mother and

grandfather, who have been circling around each other, somehow coalesce, each leaning closely into the other, standing at an angle as if listening out for an image of beauty which might re-unite the family. The immense ten- derness of the moment, caught in arrested motion, seeps back into the gentle contours of

Copyright Newspaper Licensing Agency. For internal use only. Not for reproduction.

Date: 20 July 2018

Page: 20

Circulation: 32166 Readership: 96498

Size (Cm2): 767

AVE: 2531.10

Display Rate: (£/cm2): 3.30

the music, and yields a strange feeling of inti- macy with the usually mysterious and emo- tionally distant royal house of Allemonde.

The sense of watching a kind of pared-down ballet grows, as Golaud is welcomed back into the family and Mélisande introduced to them. The music is on tenterhooks at this stage, barely able to catch its breath, and the delicate state of relations between the characters, the balance of anxieties and tensions and the vari- ous requirements of affection and ritual, prece- dence and hospitality, are borne out in the way Herheim has the characters move in and out of each other’s orbit, as if the forces of attraction and kinship that operate between the members of this complex, taciturn but volatile family could be explained purely by the laws of gravi- tation. And indeed, the movement on stage matches perfectly the shifting focus of Debussy’s music and the way it settles, butter-

fly-like, on particular colours and motifs before being swept away by more powerful and fundamental forces; this illuminates how at its heart, Maurice Maeterlinck’s troubling and mysterious symbolist drama is basically about the tensions and paradoxes implicit in the laws of human attraction.

Another aspect, borne out in the distinction between Pelléas and Golaud, relates to ways of seeing. The two half-brothers live after all in the same castle with the same people, but they rarely see the same things. In the music, this is expressed through the contrast between the light and flowing lines of Pelléas and the dark and troubled contours of Golaud, and in the way Mélisande’s ambiguous harmonic world, though caught between the two, seems so ineluctably drawn to the former. Herheim enhances this by making Pelléas a painter, ill at ease with the feudal life of the castle but fluent in exploring its beauties. The third scene’s exploration of the kingdom becomes a tour of the organ room’s paintings, some of them works in progress, others new acquisitions brought home by Golaud on his recent journey with Mélisande. The contrast between Pel- léas’s concern with the look of things and Gol- aud’s desire to hunt and possess the objects of his awareness reaches its apex in their different

attitudes towards retrieving Mélisande’s lost ring, and in the ecstatic but all too fleeting music when the cave is illuminated with moonlight.

The soloists and orchestra are wonderfully responsive to Ticciati’s musical direction and seem entirely at one with Herheim’s under- standing of the drama. Christina Gansch gives a tremendously affecting performance as

Mélisande, while the distinction between Christopher Purves’s tortured and violent Golaud and John Chest’s ethereal Pelléas matches the framework perfectly. Brindley Sherratt’s Arkel is also affecting. Herheim’s pursuit of the logic of these characterizations can lead to odd conclusions, but the direction is always revelatory on some level, even though particular details take longer to digest than others. The action concludes, perhaps predictably, by returning to the opening funeral setting, showing the circularity of the family’s thirst for renewal. At the end, though, the characters melt away – an effect aided by Herheim and Tony Simpson’s extraordinarily dynamic lighting designs – and the room is suddenly filled with contem- porary opera-goers and tourists, keen to take in the organ room before progressing to the performance, accompanied by the luminous, peacefully lapping movements of the final bars. Again, it sounds arch, but the concern here seems to be not somehow to implicate the audience in the objectification of Mélisande so much as to illuminate how we all contribute to maintaining the mythical spaces that give life to the opera.

The mysterious laws of human attraction and gravitation are equally the subject of the Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño’s first novel, The Skating Rink, in which a constant shifting between three narrators, and a focus on how each sees particular details in different ways, are used to gradually frame and explore the mysterious murder of Carmen, a beggar who once sang at the opera in Naples. Her body is discovered on an ice rink, built in secret with municipal funds in the swimming pool of an abandoned mansion. All of which makes it an unusual choice for operatic treatment – and yet

Copyright Newspaper Licensing Agency. For internal use only. Not for reproduction.

Date: 20 July 2018

Page: 20

Circulation: 32166 Readership: 96498

Size (Cm2): 767

AVE: 2531.10

Display Rate: (£/cm2): 3.30

somehow, in an ambitious new commission by Garsington Opera, the composer David Sawer and librettist Rory Mullarkey, together with the director and designer Stewart Laing and the conductor Garry Walker, manage to pull it off in one of the summer season’s most surprising triumphs.

Each narrator is given a single act – the drop- out poet Gaspar (Sam Furness), his smooth friend Remo (Ben Edquist) and the corrupt but still quite lovable town official Enric (Grant Dyle). The balance between narrative and action is managed superbly well, and the music fizzes with complexity, realizing its potential in a dizzying palette of styles but uniting in carefully structured rhythmic devices which seem to drive the action forward at break-neck speed – often faster than the characters would appear to be comfortable with. For a new, ambitious production, the musical standards are very high indeed. Each of the narrator-so- loists navigates the shifting between narration and interaction brilliantly, as well as capturing their contrasts in tonal colour and movement. Fine performances are also given by Susan Bickley (as Carmen), Alan Oke (as Rookie), and Lauren Zolezzio as the skater Nuria who, like Mélisande, is the object of fascination who brings together this fleeting community of nar- rators. The most surprising detail of the eve- ning, however, is that Laing’s clever, minimalist set is constructed on a kind of plas- tic which actually functions as a skating sur- face. Zolezzio – and more importantly her character-double, the skater Alice Poggio – can thereby give us a glimpse of the grace and beauty of movement that first brought the three conflicting narrators together.

Copyright Newspaper Licensing Agency. For internal use only. Not for reproduction.

Date: 20 July 2018

Page: 20

Circulation: 32166 Readership: 96498

Size (Cm2): 767

AVE: 2531.10

Display Rate: (£/cm2): 3.30

John Chest as Pelléas and Christina Gansch as Mélisande

Copyright Newspaper Licensing Agency. For internal use only. Not for reproduction.

Another good Crit.

Garsington Opera at Wormsley – The Skating Rink

Thursday, July 05, 2018 Opera Pavilion, Wormsley Park, Buckinghamshire, England

Reviewed by Alexander Campbell

Shares

A murder mystery doesn’t necessarily sound like an idea that will work, but there have been stranger inspirations for opera plots. Rory Mullarkey has adapted Roberto Bolaño’s novel skilfully. Each Act tells the same story seen from the perspective of three of the protagonists. With each repetition there are important additions as the motivations or perceptions or influences – of or on – these characters become drawn in more depth. As these facets are revealed the viewer may have to challenge some pre-conceptions.

Since there is a murder we also need to know who stabbed the mezzo-soprano and that is revealed at the end (in opera it’s never over until…). The plot revolves round the differently focussed desires of two men, Remo and Enric, for the ice-skater Nuria. When she loses her funding Enric illegally provides her with a skating rink in the basement of a disused palace, embezzling local-government funds to fund the operation. Remo desires Nuria sexually, and jealousies erupt when his boss, Enric of course, discovers their relationship. Enric is under pressure from the politically ambitious Mayor of the seaside town reliant on tourism to clear the city of vagrants. He orders Remo to enact the clearance policy, but when the night-watchman Gaspar is tasked to evict two females, the manipulative singer Carmen and her friend Caridad, he reluctantly does so but falls in love with the latter. Seeking to help her he follows her to the palace where she has sought refuge and he discovers the rink. Carmen has also discovered it and blackmails Enric with seemingly fatal consequences. She is found by Remo stabbed to death.

Within the structure imposed by the libretto David Sawer has also woven in some clever stylistic repetitions, adding a satisfying cohesiveness. The action is narrated by Gaspar, Remo and finally Enric. Musically, each one introduces themselves, but the first scene of each narrative sees them interacting with one other character who they introduce. These encounters drive the action. Sawer has created a score full of mystery and at times seeming simplicity, and the vocal lines are attractive with scope for dramatic characterisation: every word of the text is audible.

Gaspar has lyrical lines generally voiced over a cushion of cool string sound. The lady Mayor, Pilar, given a superlatively biting interpretation by Louise Winter, has very angular writing often punctuated by bursts of brass. Some of the most beautiful music is given to Enric – his Act Three scene where he dreams he can skate (marvellously realised in the staging) is full of rich lyricism. Praise to for the wonderfully vital and responsive Garsington Opera Orchestra under Garry Walker; translucent textures, rhythmic brio – especially in the jaunty dance sections. There is also great intensity when needed. Stewart Laing’s staging is also very effective. Likewise the small army of extras depicting the life of the town’s inhabitants have a fluidity of movement which is unobtrusive and realistic.

Garsington has assembled a great cast. The focus is Grant Doyle as Enric. He sings with burnished tone throughout and is dramatically effective. Ben Edquist brings a more slender tonal quality to the macho Remo and Sam Furness a honeyed intensity to Gaspar’s lines. Susan Bickley is, as ever, impressive and engaging as Carmen. She projects ferocity and menace and yet can also beguile. Alan Oke’s Rookie also provides brilliant vocal contrast in defining this drop-out character. Lauren Zolezzi is a warm-voiced and sensitive Nuria, and Claire Wild makes much of Caridad. Hats off to Garsington!

- Recorded by BBC Radio 3 for future broadcast

- Further performances on July 8, 10, 14 & 16

- www.garsingtonopera.org

Excellent Opera Today Crit for The Skating Rink.

The Skating Rink: Garsington Opera premiere

Having premiered Roxanna Panufnik’s opera Silver Birch in 2017 as part of its work with local community groups, Garsington Opera’s 2018 season included its first commission for the main opera season. David Sawer's The Skating Rinkpremiered at Garsington Opera this week; the opera is based on the novel by Chilean writer Roberto Bolano with a libretto by playwright Rory Mullarkey.

The Skating Rink, Garsington Opera

A review by Robert Hugill

Above: Alice Poggio (Nuria skater)

Photo credit: John Snelling

, though not without lighter moments.From Morning Till Midnight seems something of a return to the darker, expressionist world of The Skating Rink, with a libretto by Amando Iannucci, perhaps failed to quite find its mark when premiered by Opera North in 2009. This new piece, Skin Deep , to his own libretto based on a Georg Kaiser play, was premiered with some success by English National Opera in 2001, though his second opera, in fact an operetta, From Morning Till MidnightThis is Sawer's third opera. His first,

Bolano's novel tells the same events from the points of view of three narrators, each of whom is involved in a different way in the events in a 1990s Spanish town on the Costa Brava, where love leads Enric (Grant Doyle) to build an illicit ice skating rink so that Nuria (Lauren Zolezzi and Alice Poggio) can train, but the murder of a former opera singer Carmen (Susan Bickley), now living on the streets, clouds issues.

Rather daringly, Sawer and Mullarkey take this structure into the opera: each of the three acts tells the same events from a different point of view. First, that of Gaspar (Sam Furness) the night watchman at a holiday camp, tasked with evicting Carmen and Caridad (Claire Wild) and in love with the latter, who eventually discovers the illicit rink. Then, Remo (Ben Edquist), Gaspar's boss, who is in love with Nuria and thinks that he has a relationship with her. And, finally, Enric (Grant Doyle), the fat and unlovely head of the town's social services whose obsession with Nuria leads him to build the rink for her. Each act advances the plot slightly: the first ends with the discovery of the rink, the second with the discovery of Carmen's body, and the third with the arrest of Enric. Then, in a Coda, we find out who really did the murder.

The result is rather multi-layered, the characters are unwrapped rather akin to a Baroque opera, in that we first see Enric through the eyes of Gaspar and Remo before we hear his point of view. Key moments are enacted three times, notably the eviction of Carmen and Caridad, but each time in a different context. Also, rather daringly, each of the narrators actually addresses the audience: Sawer and Mullarkey stop time and allow the narrators to address us and explain themselves. This means that some of the action is described rather than experienced. Again, this creates a complex multi-layering, the sort of remove from filmic naturalism which is essential when creating an opera and this new piece is thankfully anything but a sung play.

Ben Edquist (Remo), Lauren Zolezzi (Nuria). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

David Sawer is noted for the drama of his orchestral works, and he uses the orchestra in The Skating Rink to create, colour and animate the atmosphere. The orchestra becomes another protagonist and whilst Sawer's harmonic language might be complex and sometimes challenging, his textures and ear for timbres made the music often seductive and accessible. This is a highly coloured score, which reflects the subject matter, and Sawer weaves into it popular references, yet never directly. Having the opera singer Carmen entertaining in a cafe created a magical scene at the end of Act Two, and Act Three included a disco which managed to mix drama with a popular beat, not to mention actor Steven Beard doing a wonderful karaoke number! And, the use of a brass-band (off-stage and walking on), created some wonderfully Ivesian counterpoints.

It helped that Sawer and Mullarkey had created some strongly characterised, not to say meaty roles so that Garsington Opera's cast of singing actors had something to get their teeth into. Whilst this is not an opera that you will come out of singing the tunes, Sawer's vocal lines, though sometimes complex, were dramatic, enlivening and expressive; he never noodled. For the passages where the narrators addressed the audience directly, Sawer chose a simpler, plainer style, a more neutral type of discourse which threatened sometimes to lack dramatic interest.

Stewart Laing's production did not aim to give us naturalism. We never saw the Palacio Benvingut where the skating rink was built; instead, we had to rely on the descriptions from the characters. The basic set was a space with a backdrop of a plastic curtain, which evoked those found in caravans of the period, and the stage littered with packing cases. A mobile box structure became Gaspar's office, Remo's home and Enric's office, moving about as necessary. Other elements, such as tables and chairs were brought on, and the front of the stage had a boardwalk. Yet, throughout the first act we asked ourselves, where was the skating rink? In fact, it was there all the time, the floor of the stage was covered with a special material which enabled Alice Poggio to skate on it. (One of the male actors also skated, providing a dream image of Enric as he imagines skating on the ice.) Where necessary, the cast brilliantly evoked the trickiness of walking on ice with unsuitable footwear.

Alan Oke (Rookie), Susan Bickley (Carmen). Photo credit: John Snelling.

This was very much an ensemble production. Characters emerged and then retreated, and each singer gave a committed, engaged and engaging performance. Sam Furness was wonderfully passionate as the young Gaspar, whose obsession with Carmen's companion Caridad (Claire Wild) sets the plot in motion. Furness produced a fine stream of firm tone and strong emotion. This was a thrillingly committed performance. As Remo, Ben Edquist (making his UK debut) was cooler and emphasised the character's lack of self-reflection. Rather sex-obsessed, he never understands his relationship with Nuria (the tantalising Lauren Zolezzi), and is puzzled when she evaporates. Edquist has the work's final words, slightly enigmatic and wonderfully evoking the character's puzzlement at life. As the final narrator, Enric, Grant Doyle was particularly impressive having taken on the role at relatively short notice to replace an ailing Neal Davies. At first, we see Enric through others' eyes, fat, unlovely and rather nasty, and only in the last act do we find the passion and obsession underneath. Doyle gave a beautifully crafted, multi-layered performance which really brought the character alive and, surprisingly, made us begin to sympathise with him.

The limitations of Sawer and Mullarkey's approach was the other characters were slightly less well drawn. There was no authorial voice and this meant that we never heard things from Carmen, Caridad or Nuria's point of view.

Susan Bickley was superb as Carmen, fierce, troubled and rather crazed, yet complex, and revealing elements of the person she used to be in moments like her singing in the cafe, and her blackmailing of Enric (having discovered the skating rink, built with embezzled council money). Claire Wild was evocative as the troubled Caridad, whom we only saw her through Gaspar's eyes. Lauren Zolezzi really brought out the mystery and sense of contained distance in Nuria's character, as we see her through both Remo's eyes and those of Enric. And, she was allowed to develop most, as we learned more about her in the coda. The movement between Zolezzi as singing Nuria and Alice Poggio as skating Nuria was beautifully done, and the result was a very real character.

Louise Winter (Pilar), Grant Doyle (Enric). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

The role of Pilar the town's mayor might have been relatively small, but Louise Winter really made it count. Alan Oke was Carmen's would-be lover Rookie. Also living on the streets, the two have a love-hate relationship with a wonderful shouting match which concluded Act Two. Rather underused in the three main Acts, Oke created Rookie's character using a breathy form of sprechstimme, which blossomed in his final solo in the coda which revealed the truth of the murder in thrilling fashion.

Under Garry Walker's expert guidance, the orchestra drew a wide range of colours and textures from Sawer's score, giving as thrilling and committed performance as the singers on stage and making the piece really count.

Sawer and Mullarkey have created a new opera with a striking voice, one which managed to draw an enthusiastic response from a very engaged audience, without ever seeming to talk down and with music which was of admirable complexity and sophistication. The drama was handled in a confident fashion which really made you want to know what was going to happen. The whole received a strong performance from both cast and orchestra, and it is being recorded by the BBC for broadcast later this year on BBC Radio 3.

Robert Hugill

David Sawer & Rory Mullarkey: The Skating Rink

Ramo - Ben Edquist, Gaspar - Sam Furness, Enric - Grant Doyle, Carmen - Susan Bickley, Caridad - Claire Wild, Rookie - Alan Oke, Nuria - Lauren Zolezzi, Pilar - Louise Winter, Nuria (skater) - Alice Poggio; Director & design - Stewart Lang, Conductor - Garry Walker.

Garsington Opera, Worsley; Thursday 5th July 2018.

Send to a friend

The Observer crit of The Skating Rink

Last year, Garsington Opera staged a successful new community opera,Silver Birch. This year they have their first world premiere on the main stage,The Skating RinkbyDavid Sawer, with a libretto by Rory Mullarkey based on the Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño’s novel. Told from three perspectives, the opera is set in a seedy Spanish seaside town, late season. Three narrators piece together the story: Gaspar (Sam Furness), the poet-campside attendant; Remo (Ben Edquist), a shiny businessman; and Enric (Grant Doyle), the paunchy civil servant prepared to embezzle local funds for love, building an ice rink for the skater, Nuria (Lauren Zolezzi), object of his and Remo’s passion. Other characters, including two homeless women – persuasively sung by Susan Bickley and Claire Wild – exist on the fringes of society. Alan Oke shows a new, foul-mouthed side as the vagrant, Rookie.

Adroitly staged and designed by Stewart Laing – a few tents, a boardwalk, a multipurpose, Perspex cabin – The Skating Rink grows in intensity with each act. Tough verbal exchanges are offset by magical, chilly instrumental music for the skating scenes, plucked, spiky sounds conjuring an icy underground world. Zolezzi’s double as Nuria, the skater Alice Poggio, pirouetted and twirled on the artificial ice rink, transporting us far from Buckinghamshire heatwave discomfort.

Sawer’s imaginative scoring, using a small ensemble with saxophone, harp, guitar and ukulele-like charango adding Latin accents, shifts freely but precisely from set piece (song, marching band, karaoke scene) to through-written fluidity. Cast and orchestra, conducted by Garry Walker, served the music admirably. I wasn’t engaged by Bolaño’s novel – my shortcoming; it is much admired – but Sawer and Mullarkey gave it heart.